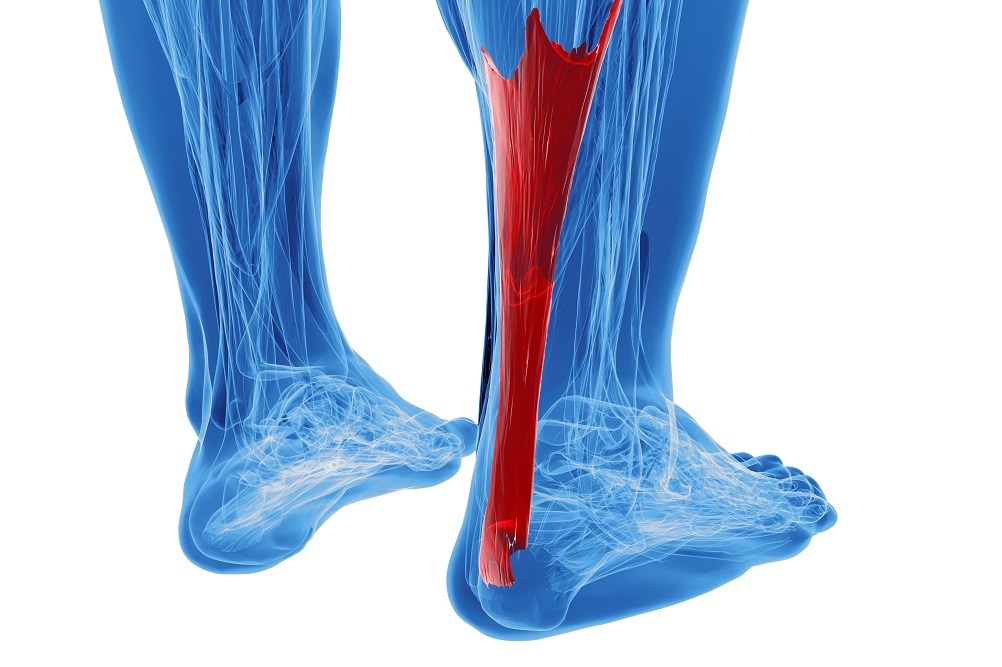

Achilles tendinopathy is a common, yet potentially debilitating injury in which load can be both anabolic and catabolic (Cook and Purdam., 2008). There are multiple contributing factors to Achilles tendinopathy and rehabilitation can often be difficult and prolonged (Kountouris and Cook., 2007).

Diagnostic criteria for Achilles tendinopathy

When diagnosing Achilles tendinopathy, the main diagnostic criteria is patient history and pain on palpation over the tendon (Maffulli, Kenward, Testa, Capasso, Regine and King, 2003). Cook, Khan and Purdam (2002) suggest that Achilles tendinopathy results in local pain over the Achilles tendon and does not refer elsewhere. The other diagnostic criteria are direct relationship

between worsening of symptoms and increase in training load and load related pain (Cook, Khan and Purdam., 2002). Gymnastics is an example of a sport which puts individuals in a high-risk category for Achilles tendinopathy with incidence as high at 17.5% due to the excessive plantarflexion and high recoil aspects of this sport (Emerson, Morrisey, Perry and Jalan., 2010). If a patient has an isolated location of pain over the mid-portion of the tendon, this decreases the likelihood of differential diagnoses such as sever’s disease, avulsion fracture of the calcaneus or insertional tendinopathy (Adirim & Cheng., 2003). Gradual onset of symptoms that warm up 5-10 minutes into training, stiffness during exercises and decreased function/muscular endurance of the calf are also characteristic of a tendinopathy (Joyce and Lewindon., 2016).

Causative factors of Achilles Tendinopathy

It is now widely documented that the causes of Achilles tendinopathy are not well-known and diagnosis may be complicated due to close proximity of numerous other soft tissue structures (Hutchison et al., 2012; Kader, Saxena, Movin & Maffulli, 2002). Causative factors include both extrinsic factors such as training load and potentially poor technique and intrinsic factors such as family history, collagen make-up, muscle/tendon strength, biomechanics and previous injury history (Abate et al., 2009).

Training load/repetitive stretch-shortening cycles

Increased training volume that coincides with onset of symptoms is one of the biggest predictive factors for developing a tendinopathy (Cook, Khan and Purdam., 2002; Clement, Taunton and Smart., 1984; Abate, Gravare-Silbernagel, Siljeholm, Di Iorio, De Amicis, Salini, Werner and Paganelli 2009; Joyce and Lewindon., 2016). For example, Gymnastics and trampoline require high levels of repetitive, explosive/plyometric loads with up to 6-8x body weight being absorbed in running, hopping and jumping (Malliaris and O’Neill., 2017). When the tendon is overloaded there is a breakdown of the quality of tissues within the tendon which causes inflammation and degeneration (Notarnicola, Maccagnano, Di Leo, Tafuri and Moretti., 2014). Repeated loading through an injured tendon results in micro-ruptures occurring due to the breakdown of cross-links by collagen fibres sliding past one another (Abate et al., 2009). This cumulative micro-trauma leads to a change in ground substance, collagen disarray and increased vascularity which therefore decreases tensile strength (Abate et al., 2009; Brukner and Kahn., 2007). Type 1 collagen fibres, which make up normal tendons, are often replaced with Type 3 collagen in injured tendons which makes the tendon weaker due to a decreased volume of cross-links between and within the tropo-collagen units (Kader, Saxena, Movin and Maffuli., 2002).

Biomechanics/Strength & Stability

Sports such as gymnastics require a large amount of controlled jumping and landing and therefore a high level of functional motor control for these athletes. Contributing factors for Achilles tendinopathy can be decrease gluteal activation which results in reliance on passive structures through a stiff ankle and knee strategy. A stiffer knee landing strategy has been reported in runners with Achilles tendinopathy, and it is likely a protective mechanism to decrease load through the Achilles tendon (Malliaris and O’Neill., 2017). If a patient has poor static inversion this could suggest a weakness of tibialis anterior and posterior which could translate to poor stability of the right ankle. Excessive over-pronation of the foot can cause increased stress to occur at the Achilles tendon which under repetitive load can cause excessive levels of stress and can lead to injury (Hess., 2009). Decreased right calf endurance and strength is a risk factor for Achilles tendinopathy (Malliaris and O’Neill., 2017). Poor calf bulk bilaterally is likely a result of long-standing pathology.

Family history/previous injury history

Previous history of injury is an important predictor of injury, likely due to alterations in the neuromuscular system (Malliaris and O’Neill., 2017). If an athlete has a previous history of right ankle sprain this could cause altered loading patterns within the right lower limb due to potential muscle inhibition. This can affect dynamic stability of the ankle and cause altered loading patterns through the Achilles tendon (Abate et al., 2009). If there is also a hereditary history which could suggest potential predisposition to Achilles tendinopathy as variations within the type V collagen and tenascin C gene have been determined to have a potential co-relation to tendinopathy (Abate et al., 2009; Xu and Murrell., 2008; Kannus., 1997).

If you have any questions or would like to book in to see one of our physiotherapists, please do not hesitate to contact Get Active Physiotherapy on 1300 8 9 10 11 or email us at admin@getactivephysio.com.au